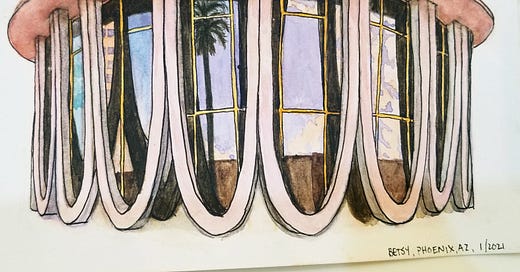

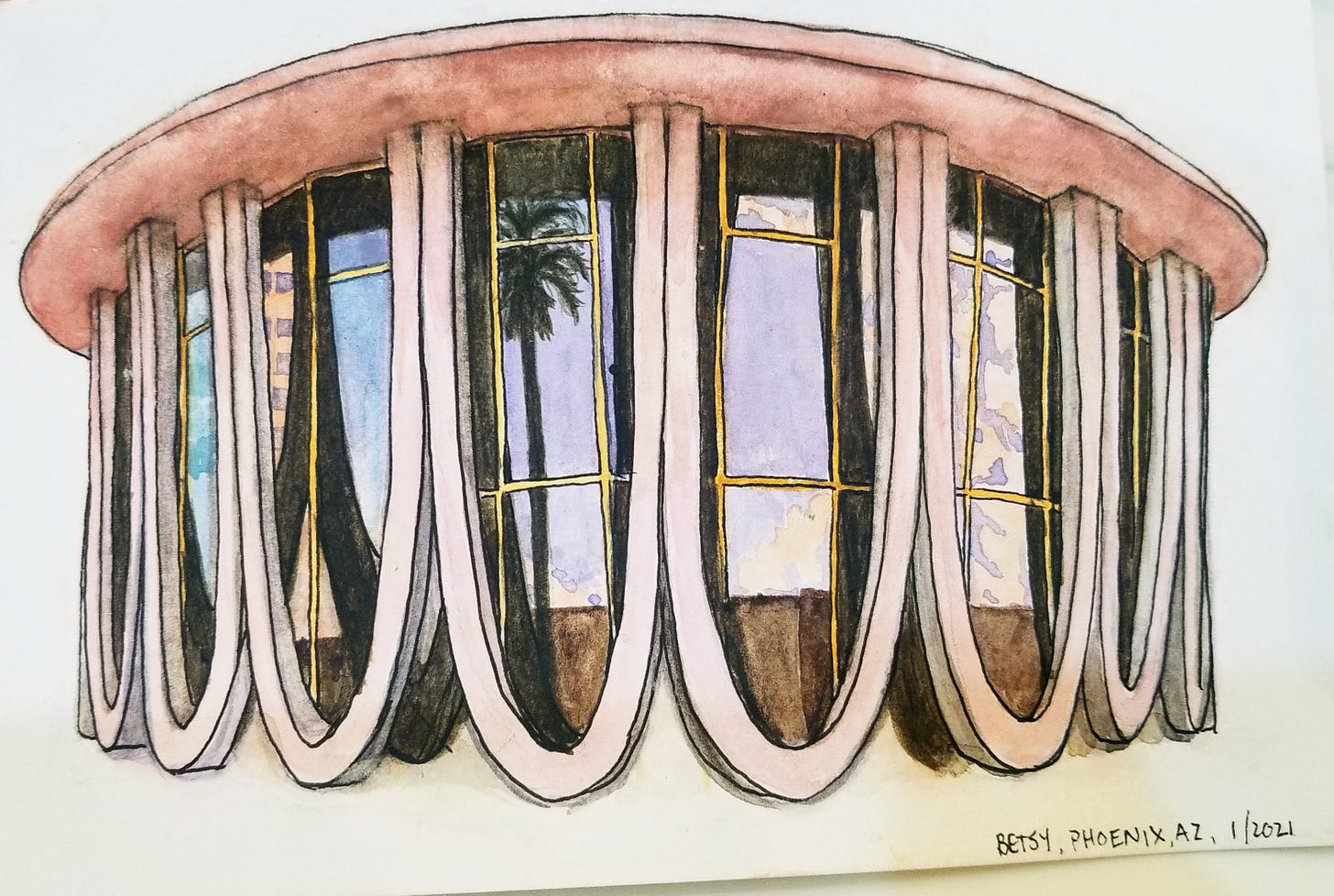

Painting by Betsy Feuerstein

For the last few months, I’ve been MIA from the newsletter because I’ve been caught up with making stories—for my day job, for the to-be book, and for an article that at last came out. So instead of writing about a couple of social science papers here, I’ll point you to my latest Atlantic feature, which is about partners who schedule times for disagreement. Come for the insight on managing anger and grievances in close relationships, stay for the moments of weirdness and delight from the partners I profiled. Like the couple whose first interaction was an hours-long argument with each other.

Here’s a little preview of the piece. A psychology professor is commenting on a system that Kristen Berman and Phil Levin created: this couple only talks about big decisions at quarterly meetings.

Córdova likens Berman and Levin’s system to “worry time,” a technique used in cognitive behavioral therapy in which patients note what they’re feeling, set their worrying thoughts aside, and reengage with them at a designated time. It’s the difference between having dirty clothes strewn across a room and having those same garments tucked in a laundry basket. The laundry has to be done either way, but if it’s in a basket, you don’t have to be reminded of it every time you open the door.

I can’t stop thinking about:

Sounds: This interview with the author of The Body Keeps The Score—a bestselling book about trauma—is a fascinating conversation that pulls together so many things I’ve been thinking about: the way we draw a line between the mind and body and regularly privilege all things cognitive; how moving our bodies can affect our emotions; how adults—not just children—need play!; how grieving has become less collective and more individualistic over time; and the healing potential of Internal Family Systems Therapy (I linked to a feature about this form of therapy in an earlier newsletter).

Video: For a brief shot of adorableness, watch this video about first-day-back-at-the-office jitters.

Now you know:

Gene therapy for Tay-Sachs disease is tested not in mice or rats who are given the disease, but in a rare breed of sheep that has naturally occurring Tay-Sachs. This is the case because a couple of farmers noticed that two of their lambs had some sort of neurological issue, which, much later, scientists discovered was Tay-Sachs. The farmers donated the lambs to a veterinary school.

I’m featuring artwork/crafts by friends and readers. Send me a photo of any art of yours that you’d like me to include in a future newsletter.